Power for All: Energy access trends for 2021

2020 reminded us why it can be risky to make predictions. Sometimes the unpredictable alters the normal march of progress. Enter COVID-19, and…well, you know the rest.

But the world goes on and so too does the energy access sector, thanks to the dedication and passion of the people in it, who worked tirelessly last year to minimise an industry crisis that battered decentralised renewable energy (DRE) companies and consumers alike and reversed nearly a decade of progress.

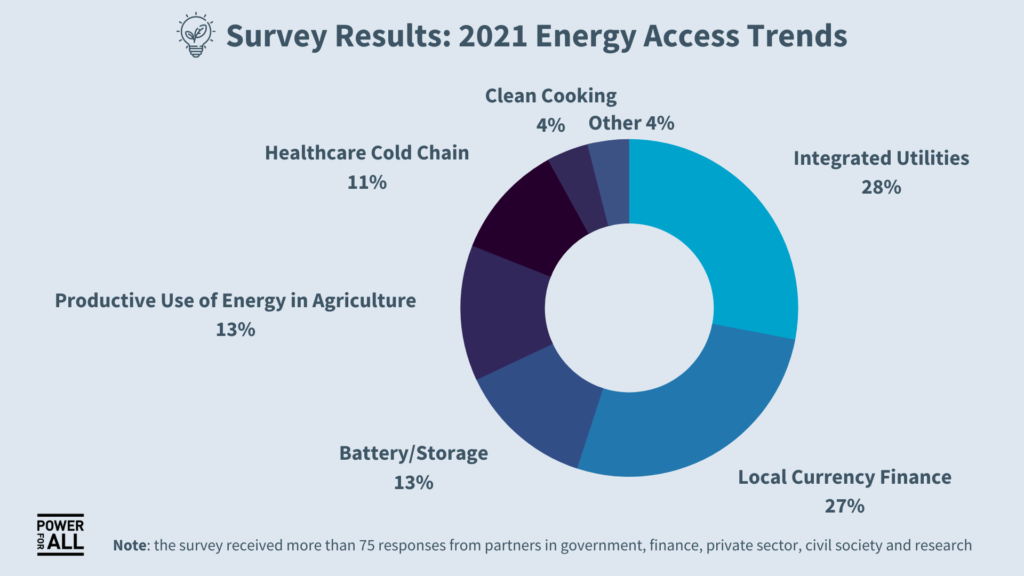

So what are the top energy access trends we expect to see in the year ahead for decentralised renewable energy? This year, to better inform our annual top trends list, we crowdsourced ideas for the first time through an open survey, receiving input from more than 75 of our partners (investors and donors, international and national trade associations, companies, government, civil society, researchers), and we also interviewed leading market analysts, including Bloomberg New Energy Finance (BNEF) and Wood Mackenzie, for their perspectives (be sure to dig into those by listening to our two podcasts).

Certainly the recovery from and the response to the pandemic will continue to be a near-term focus for our sector (expectations are for a recovery in consumer demand and investment, albeit uneven, starting in Q2), but we treated that as a global macro-trend impacting all markets and have not included it specifically in this year’s list. Similarly, there was consensus that distribution of a COVID-19 vaccine will ensure that the link between energy access and universal healthcare will be a key trend of the year, so we included it in our list, but also dedicated a deeper look at the topic and what to expect.

Below, in no particular order, you will find the Power for All annual energy access trends for 2021, and a visualisation of the survey results. (Revisit predictions for 2020 and 2019 as well).

- Tariffs and the integrated energy tangle/tango. “The off-grid and on-grid worlds are really starting to bump into each other,” says Wood Mackenzie analyst Ben Attia. According to experts surveyed, the main collision point is tariffs and subsidies. It is clear that utilities and regulators in Africa and Asia have finally woken up to the fact that decentralised renewables are a force to be reckoned with. What’s also clear: their reaction is all over the map (literally). India’s government, exhausted from three costly and ineffective bailouts of state-owned utilities over the past two decades, is pushing privatisation of distribution networks, which minigrid developers are moving to take advantage of. Also in Asia, Myanmar is welcoming greater private sector involvement, while the Philippines is considering the same.

In sub-Saharan Africa, where all but two utilities lose money despite being heavily subsidised, the story is mixed. Many countries in western Africa (Nigeria, Togo, Ivory Coast) are looking to the private sector, while those in eastern Africa seem less sure: Tanzania, once a poster child for off-grid regulation, has politicized tariffs and cracked down on private companies, while in Kenya a debate rages about the bankability of utilities as decentralised renewables eat into the market. Wrapped up in all of this is tariffs, subsidies and vested interest. With different dynamics in different countries, the only prediction we feel confident in making: it’s going to be a wild ride. Some have called for a “grand bargain” between the public and private sectors that relies on integrated energy planning. Others, including the Utilities 2.0 initiative and Konexa, are trying to show how that bargain actually works in practice, and prove its mutually beneficial nature. Tariffs charged by the private sector are expected to be “cost reflective”. But until one of two things happens — either state-owned utilities are held to the same standard on cost-reflective tariffs, or private companies are subsidized on par with utilities — true integration will remain out of reach. “As the two worlds start to collide,” says Attia,” there’s some really good symbiosis and we could see some glass break.” How tariffs are handled (and subsidies that shape those tariffs) will largely determine the outcome. And the implication from that? National governments and their policy and regulatory frameworks will decide our fate.

- C&I: a “gateway drug” to off-grid investment scale. In late 2019, we spotlighted the rising importance of Commercial and Industrial (C&I) in scaling decentralised renewables. It now appears that this trend is finally coming to pass, and as a result it appears to be poking infrastructure capital out of its off-grid slumber. We’re already seeing movement, with companies like Rensource, DPA and Husk Power starting to achieve scale with corporate off-takers and MSMEs. Analysts say that many investors focused on energy access started in solar home systems, graduated to mini-grids, and are now graduating to C&I. But the reverse dynamic is also now in play: investors starting to get their feet wet in frontier markets in C&I may move down to look at minigrids and solar home systems once they understand the markets and customers better. Wood Mackenzie analyst Ben Attia thinks C&I can act as a “gateway drug to lower-tier consumption.” This uptick in investor interest is also producing some new approaches, including a revamping of the anchor-customer model, with a C&I customers serving as anchor loads, and residential customers layered on top of that (almost a quasi-minigrid).

Developers are also adding adjacent services (LPG, energy efficiency) and becoming customer-centric service providers. Adds BNEF’s Takehiro Kawahara: “It’s not only on-site solar, but also pay-as-you-go for C&I customers,” citing an East African joint venture between a local company and a Japanese air conditioner manufacturer to provide cooling on a pay-as-you-go basis to commercial customers. As this market segment grows, and as we see more portfolio aggregation and securitisation across the sector, infrastructure investors are expected to take a second look at off-grid by the end of 2021, early 2022, the analysts said.

- Garbage in, garbage out: better SDG7 tracking, or #stopguessing. It’s a common trope in business that you can’t manage what you can’t measure. Sustainable Development Goal 7 (SDG7) is no different. Based on current tracking methods, it is clear that we are far off course in our bid to achieve universal energy access by 2030, both for electrification and cooking. What’s just as clear: what we’re currently measuring for SDG7 does not accurately capture energy poverty and therefore, according to IIASA, we’re even further behind than we think. Their new framework suggests measuring energy poverty by appliance ownership, not only by energy consumption (consumption is misleading because it does not translate into more service if appliances being used are inefficient, yet it still informs investment and policy decisions). Besides a new lens on measurement, greater ambition on the minimum per person annual energy consumption required by SDG7 is needed, according to Energy for Growth Hub, which called for increasing the minimum to 1,000 kWh from 50 kWh. But updating the official indicators for tracking success in SDG7 is needed, according to Energy for Growth Hub, which called for increasing the minimum to 1,000kWh from 50kWh. But updating the official indicators for tracking success in SDG7 to include service provision and higher consumption levels is a major challenge. Although there is an UN inter-agency expert group focused on indicators, any changes require global consensus, which is very difficult to achieve, despite the fact that affordability and other aspects of service quality are critical missing pieces of the measurement puzzle. Action is more likely at the country level. Some nations have suggested additional indicators and alternative measurement frameworks, and there is also a lot of discussion on enhancing data collection for better indicator development and regular tracking. Most data collection has used surveys up till now, but it also requires using earth observation and other big data sources to enable more real-time tracking of progress, as stressed in this just released analysis.

Without question, the absence of more and better data remains a serious constraint across the board for SDG7 (a range of players are helping — eGuide, Odyssey Energy Solution, TFE Energy, 60 Decibels), and much more is needed on numerous topics, but we can’t accurately address other data gaps until we have a reality-based measurement of energy poverty itself.

- Pooling concessional $$ and mobilising climate $$. The COVID-19 crisis prompted a level of cooperation among energy access stakeholders never seen before. It highlighted the need for such collaboration, but also showed how lacking it is on an ongoing basis. Not surprisingly, funders are coming under increased scrutiny due to lack of a coordinated, efficient and rapid approach that’s partly to blame for a huge gap in financing (significantly increased disbursements of about $45 billion per year between now and 2030 “are urgently needed“). Mechanisms for donor coordination do exist, both at the national level and internationally. The Mini-Grid Funders Group, for example, has been around for a while (see their recent less-than-inspiring response to a failure to disperse promised funds) and recently added the US International Development Finance Corp (DFC) and IFC, and a Household Solar Funders Group was recently created as well. But the fact is simple: there are far too many individual funds and far too many vanity projects that take away from the potential to pool scarce concessionary funds and use that money to derisk larger pools of money from commercial and social impact investors. The Rockefeller Foundation is taking action, recently going “all-in” by committing $1 billion over the next three years to scale decentralized renewables. It has already shown some initial success in crowding in others, including a pledge of $2 billion from the DFC. At the same time, the Universal Electrification Facility, while not yet pan-African as originally envisioned, has already kicked off in Sierra Leone and Madagascar with the support of a number of funders and is still targeting disbursement of $500 million by 2023. “In terms of financing, big organizations need to be making bigger commitments,” said Damilola Ogunbiyi, CEO of SEforALL, which is implementing the UEF. Concentrating concessionary funds into fewer vehicles that derisks commercial capital at scale: that on steroids is what is needed. But what’s also needed is the support of climate finance, which has largely ignored energy access despite the fact that energy poor countries are also the most climate vulnerable. But with COP26 later this year, and a focus on an “inclusive energy transition”, sector leaders are pressing hard to attract more climate finance. As one leading executive in the sector said: “The climate case for energy access will finally resonate. Climate investors will discover energy access.” Let’s hope so. The impact will be widespread, said one development bank representative: “with more and more funding for energy access coming from climate adaptation and mitigation budgets, this will filter through in all sorts of interesting ways”, citing research to better understand off-grid climate impact, more action on diesel genset replacement, and exciting, faster progress on interoperability, modularity, repairability, and e-waste management to improve the sector’s overall contribution to adaptation and mitigation.

- The rise of local entrepreneurs and supply chains. “Homegrown energy access companies will start to scale,” says the head of one clean energy accelerator. It started early last year with the launch of VentureBuilder, a firm dedicated to rapidly scaling local off-grid distribution companies. Later in the year, we learned why this is so important: 75% of committed off-grid capital in 2020 went to 3 international companies, despite the fact that local companies were suffering most amid the pandemic, and the fact that “local companies have an advantage in last-mile communities, given their pre-existing networks”, according to the Global Distributors Collective. Amid calls to build back better from COVID, part of that focus is on creating more local resiliency by strengthening domestic entrepreneurial ecosystems and local supply chains. To level the playing field, SEforALL has said that a capped percentage of funding should go to local energy access companies, calling for a “significant amount, like half”, noting that local companies are “doing critical work, especially in COVID times, so they need funds directed to them.” Funders surveyed agreed on the need. “We will spend the year learning and discussing how to do it, what is needed to do more of it, what are the barriers preventing it today,” one investor said. (Read this great perspective to fast-track that learning process.) Meanwhile, we predicted that local manufacturing would be the “next frontier of SDG7” in 2019. That was perhaps a bit premature. But disruptions to global supply chains due to COVID, and an understanding among the most climate-vulnerable countries that the pandemic was just a dress rehearsal for major climate disruption, have created a spotlight on doing more to build resilient supply chains closer to home. IRENA stressed this need to build up local supply chain in its post-pandemic recovery recommendations.

- Food systems and the business case for decentralised renewables. 2021 will see the first-ever UN summit focused on food systems, as well as the first UN high-level dialogue on energy in four decades. As such, it will be a critical year for creating alignment and action between SDG2 (zero hunger) and SDG7 (universal energy access). Much has been made on the role of decentralized renewables in scaling food productivity and food security in Africa and Asia, where agriculture is a major contributor to GDP and employment, especially for women and youth. But the opportunity is still largely untapped (with the exception of solar irrigation), largely because of an inability to pay by farmers, according the PULSE report from IFC Lighting Global, which identified an addressable market of more than $11 billion for agro-processing, solar pumping and cold storage, but because of affordability issues, only a serviceable market of less than $800 million, or just 6% of the potential. Irrigation can only be the start: with increased yields created by irrigation, farmers cannot access the added value without drying, milling, cold storage and a standardized, technology appropriate supply chain of machinery and appliances to achieve greater mechanization. This will also require helping farmers to expand beyond the farmgate, since that’s where 80% of revenue takes place (through processing, retail, etc). In order to decarbonize and electrify the entire agricultural value chain, expect to see more activity around reducing costs through end-user subsidies and bulk machinery procurement, improving supply chains for productive use appliances, and better coordination between the food, water and energy sectors to create common programs and investments, and integrated policies. A focus on net-zero cold chainis producing a lot of activity and innovation, and we expect that to be a major focus of the year given its tie-in to COP26 and the potential for emissions reductions by scaling sustainable energy refrigeration (its estimated about 11% of all greenhouse gas emissions that come from the food system could be reduced if we stop wasting food).

- It’s demand, stupid (aka diversification & customer-centricity). “Energy access is no longer the domain of just the off-grid energy companies (supply), but the users/buyers of energy (demand) as well,” said a leader at one major private foundation. As seen by the focus this year on healthcare and food systems, our sector depends on end-user demand to scale, but sufficient demand has proved elusive. The energy industry, including the access community, has a myopic supply-side bias. In some markets, utilities simply refer to customers as “rate payers” and interact only to collect payment. That’s not going to work for energy access in Africa and Asia, where last-mile service delivery is much harder and many consumers find affordability a major barrier. Fully embracing a demand-driven mindset is critical, not just for creating market pull from agriculture and other productive segments of the economy, but also for best serving all rural poor and improving their livelihoods. So while we have a lot of information about what solutions may be most affordable, we still don’t have great data on how to best meet demand. A2EI and RMI have started to put some thinking behind what’s actually possible in food production, looking first at Tanzania and Nigeria, respectively, and answering some outstanding questions about what crops are most suitable for decentralized renewables, and what’s needed (in terms of appliances, finance, business model) to help farmers access DRE-based solution. In addition, companies are increasingly diversifying their businesses by bundling additional, often higher-margin products and services, into their offering to increase demand and grow average revenue per user (ARPU). “We see a market for larger, higher-margin sales and product ranges aiming at ‘beyond energy’ models,” said the CEO of a major energy company, citing pumps, mills, cold storage, washing machines, drinking water, e-vehicles and more. A lot of thought is now going into demand-side subsidies for households, as well, since there is a growing recognition that demand will not be forthcoming for all rural poor. As one leading researcher noted: “Most households currently buying [small solar] are relatively middle class living in/around cities… every reasonable analysis tells us that hundreds of millions of people will NOT get electricity access by 2030 if we rely on grid expansion and purely commercial off-grid approaches alone.” In an effort to leave no one behind, there is growing momentum behind the need for demand-side subsidies, as outlined in this recent discussion paper. This will be even more urgent to help consumers if the pandemic continues to impact economies. poor African households cannot afford these systems.

- Universal healthcare: service-based models and off-grid medical devices. “COVID has provided a big wakeup call around the urgent need to electrify off-grid public health facilities, and extend cold chains into rural areas,” says a multilateral development bank representative. With vaccines finally being distributed, and the need for many of them to remain refrigerated at low temperatures, the issue of cold chain is keeping the need for health clinic solarization at the forefront of development for 2021. While much attention has been given to vaccine distribution, the bigger issue remains that only 28% of the more than 98,000 health care facilities in sub-Saharan Africa have access to reliable electricity, while in India about 40,000 clinics are in the same situation (see this action plan developed for India) As a result, most basic health care services in rural communities are unavailable, including lighting, neo-natal warming, sterilisation, internet and e-health access, etc.

2021 will see a major focus on solving this systemic challenge, with a focus on moving from a transactional approach to a service-based model to ensure long-term contracts for operation and maintenance at rural clinics, and increased joint planning between health and energy agencies. Also expect to see a much bigger focus on supply chain and getting clarity on how to make standardised and affordable medical devices that are suitable for off-grid areas, a critical topic that has been largely ignored. “Many governments will prioritise using clean energy for health facilities to access reliable electricity,” said BNEF’s Kawahara. “Other governments may also follow, and this will need support from international agencies and development banks.” Be sure to read a more in-depth Power for All analysis of what we can expect.

- Show me the (local) money. A major barrier to scale (which we highlighted in our 2020 trends), is the absence of blended finance, including access to local currency debt as a way to hedge against foreign exchange risk. Our survey identified local currency financing as the #2 trend for 2021. “We need to develop credit enhancement instruments to make sure local currency is available,” the head of a major UN agency said, while other investors also cite the need for structured insurance and guarantees to augment access to local debt. A recent report from the African Development Bank (AfDB) also spotlighted the importance of mobilizing local banks in support of the sector, noting that interest rates for local currency are “extremely high” because of the sector’s high-risk perception among potential lenders. A number of financial institutions such as Africa Guarantee Fund, TCX Fund and Infracredit have already started providing local currentcy financing, and expect to see transactions increase in coming months. A leading foundation executive also highlighted an increased role for micro-finance to reach underserved communities “in new and impactful ways, going beyond the restrictions we now see that micro-finance still has with respect to duration, interest-rates, collateral, risk premiums, etc.”

- Show me the (local) money. A major barrier to scale (which we highlighted in our 2020 trends), is the absence of blended finance, including access to local currency debt as a way to hedge against foreign exchange risk. Our survey identified local currency financing as the #2 trend for 2021. “We need to develop credit enhancement instruments to make sure local currency is available,” the head of a major UN agency said, while other investors also cite the need for structured insurance and guarantees to augment access to local debt. A recent report from the African Development Bank (AfDB) also spotlighted the importance of mobilizing local banks in support of the sector, noting that interest rates for local currency are “extremely high” because of the sector’s high-risk perception among potential lenders. A number of financial institutions such as Africa Guarantee Fund, TCX Fund and Infracredit have already started providing local currentcy financing, and expect to see transactions increase in coming months. A leading foundation executive also highlighted an increased role for micro-finance to reach underserved communities “in new and impactful ways, going beyond the restrictions we now see that micro-finance still has with respect to duration, interest-rates, collateral, risk premiums, etc.”

Storage and batteries. “The final death knell for lead acid batteries,” is how one aid agency executive described the dynamic behind the growing role of storage and batteries in energy access. But it’s also the death spiral of diesel generators, as well as the enabler for the emergence of eCooking, eMobility and other battery-dependent services. New battery technologies, falling prices, battery swapping business models, there is so much happening. As the Africa Energy Indaba will rightly ask in its upcoming discussion in March 2021, “Is energy storage the key to energy access?” It is certainly a big key on the key chain.

Honorable Mention

These trends also surfaced as being important to watch:

- India and the Sahel: Watch out China, India is making moves to take a share of the global distributed solar and appliance space. Talk of a $600 million World Solar Bank, leadership on refrigeration, a massive tender for nearly 10 million solar home systems for Africa that could be a model for bulk procurement for other off-grid appliances, an increased focus on solar panel manufacturing, and the launch of global SDG7 Hubs. Meanwhile, the Sahel region in Africa has emerged as the key focus area for supporting energy access, as illustrated by AfDB’s Desert to Power initiative, and recent work on the link in the region between energy and agriculture.

- Strategics: not new to our trends watch, the profile of multinationals remains high in the sector. Companies like ENGIE Energy Access are invested, vertically integrated, and not just looking at energy, but other services (cooking, internet, water). Listen to our recent interview with their CEO. Also look for African businesses with significant distribution channels to take a bigger position in the market. For a more comprehensive picture, be sure to listen to our podcast with BNEF’s Takehiro Kawahara.

- eCooking and eMobility: we called eCooking back in 2018, and have included cooking in our last two trend forecasts for 2019 and 2020, but it’s still just as important if not more so and expect to see greater policy integration between electricity access and cooking. eMobility was also on our list last year, and we expect it to make significant headway in 2021 as access to market and adjacent retail services increase in importance. One country representative for an implementation agency expects the development of national electric vehicle and electric cooking policies and roadmaps that support infrastructure and technology development, enable business models and create supporting financial mechanisms.

- Other: A grab bag of other topics worth mentioning from the survey included: 1/ streamlined project licensing (with Ethiopia as leader), 2/ skills and training (especially for youth and women), 3/ new AI and IoT for remote management (this includes peer-to-peer trading), 4/ recycling and the circular economy, 5/ interoperability between grid/off-grid and AC/DC, and 6/ the potential for Renewable Energy Certificates (D-RECs) from distributed energy as a new funding source.

Source : ESI Africa